Blog #4: Johannes Geccelli. Don't beam me up

Fast zwanzig Jahre ist es her, dass zuletzt eine monografische Publikation zu Johannes Geccelli erschienen ist. Er wäre fast in Vergessenheit geraten, der 1925 in Königsberg geborene und 2011 in Berlin gestorbene deutsche Maler. Wenn nicht … ja, wenn nicht Anna Finke vom Künstlernachlass Johannes Geccelli die Idee gehabt hätte, anlässlich des 100. Geburtstags ein Buch zu initiieren. Anna sprach mich nach der Buchpräsentation meines 2023 erschienenen Buches über Daniel Richter an: Ob ich denn Geccelli kennen würde? Und ob ich Lust hätte, eine Publikation über ihn zu machen? Das musste ich nicht zweimal gefragt werden. Natürlich kannte ich Bilder von Geccelli! Erstmals gesehen hatte ich sie als Bonner Studentin der Kunstgeschichte während meines Praktikums in der Neuen Nationalgalerie in West-Berlin 1985. Die Nennung des italienisch klingenden Namens erzeugte augenblicklich ein immer noch frisches Nachbild von Bildern, die große Freiheit und eine eigentümliche Transzendenz ausstrahlen. Ungemein konkret sind sie, minimalistisch und dazu fleißig in ihrer Machart, reihenweise einen Farbbalken präzise neben den anderen zu setzen. Es waren aber nicht nur Form und Malweise, die sich mir „eingebrannt“ hatten, sondern ebenso ein besonderes Farblicht. Die Kompositionen von genau kalkulierten, ausgetesteten Kontrasten und Überlagerungen riefen schon damals in meiner Wahrnehmung Schwingungen hervor, deren Frequenz über all die Jahre hinweg nicht verloren gegangen ist.

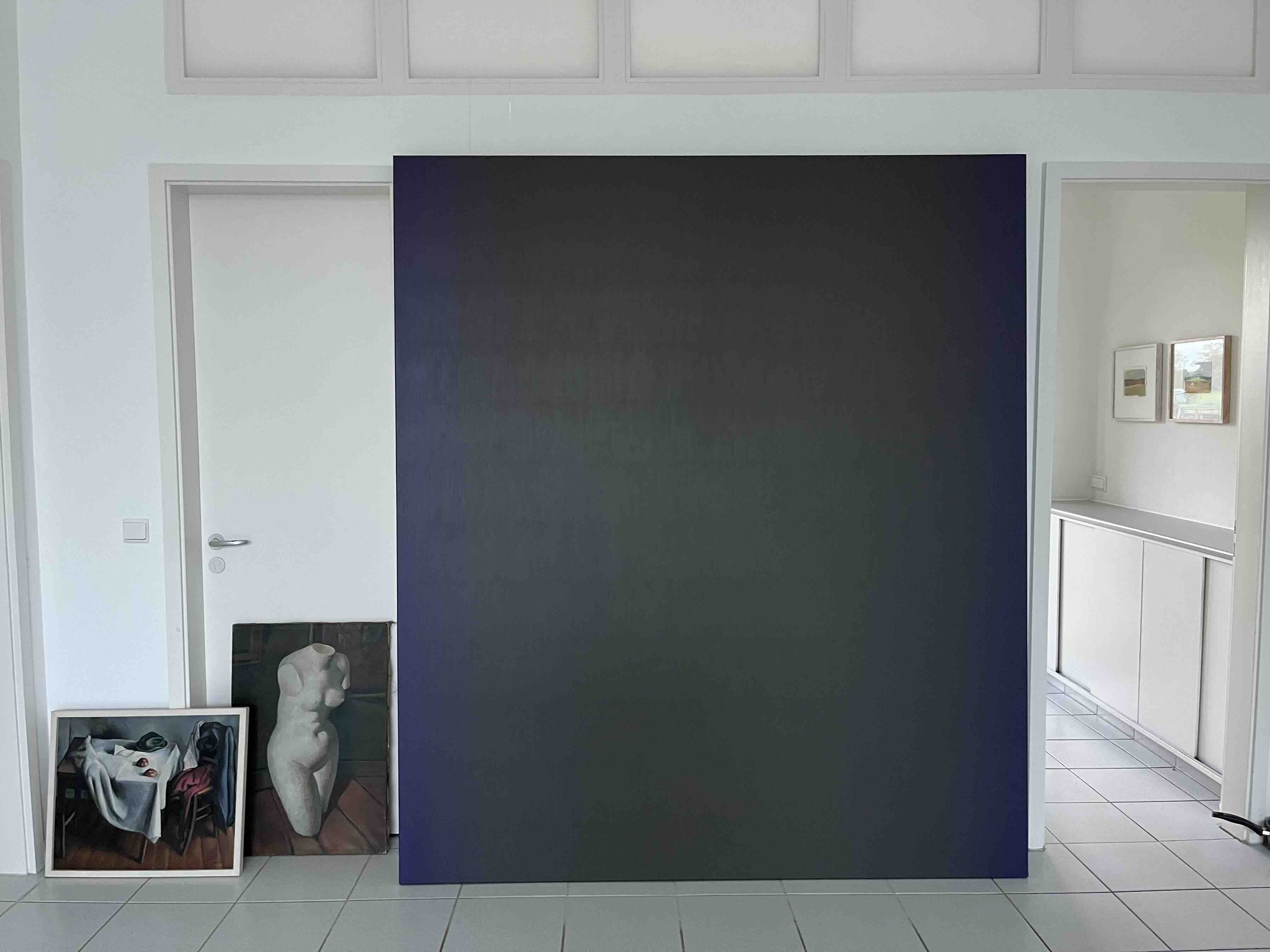

Aber wie fängt man so ein Buch an? Anna lotste mich und meinen Hund zunächst geschickt nach Jühnsdorf, aufs Land, dorthin, wo Johannes Geccelli von Mitte der 1990er-Jahre bis zu seinem Tod gelebt und gearbeitet hatte und wo nun sein Atelier zum Lager und Archiv geworden ist. Klar, dort könne man auch schön spazieren gehen, das habe der Maler selbst immer wieder getan, um seine Augen zu erfrischen. Nach meinem ersten Besuch dort war es um mich geschehen: Wie anders die Bilder im hellen Tageslicht des ehemaligen Arbeitsraumes wirkten! Und wie sich vor allem die späteren Werke ganz selbstverständlich mit der Farbigkeit der Natur draußen verbanden! Unter einem tiefen Himmel die weiten Flächen von Weideland und Äckern, durchzogen von schlammigen Kanälen (mit magischer Anziehungskraft für meinen Hund), kleine Waldungen hier und da. Als ich dann im Laufe des Projektes in wechselnder Begleitung der Grafikerin Yvonne Quirmbach, des Fotografen Nikolaus Brade und der Verlegerin Nicola von Velsen wiederholt in das brandenburgische Dorf fuhr, konnte ich mir jedes Mal sicher sein, dass dieser Ort auch auf andere Personen eine magische Wirkung ausübt.

Begeisterung allein jedoch macht noch kein gutes Buchkonzept. Mir lag daran, etwas von der Freude, Leichtigkeit und zugleich Tiefe der Empfindung, die von Geccellis Malerei ausgehen, zu vermitteln. Ich erspare uns allzu detaillierte Einblicke in die mühsamen Vorarbeiten, die einer Idee stets vorausgehen. Wie bei jedem Projekt ist eben immer erst einmal viel zu studieren, zu lesen, bisherige Textautoren sind zu bewundern oder zu kritisieren. Material sichten, seitenweise bio- und bibliografische Daten recherchieren, auflisten, auswählen. Digitale Reproduktionen der Bilder in einer Datenbank miteinander vernetzen, hin- und herschieben, dann doch noch ausdrucken und wieder auf Karteikarten kleben, Gruppen bilden, Chronologien und Genealogien verstehen. Immerhin geht es hier um ein Werk, das bereits Ende der 1940er-Jahre begann und viele Hundert Arbeiten auf Leinwand und Papier umfasst.

Nein, das konnte man unmöglich alles berücksichtigen. Also eine Auswahl an Bildern treffen und diese sinnvoll anordnen. Aber nicht von Anfang bis Ende, sondern lieber aus einem Hier und Jetzt rückwärts, um dem Werk kaum mehr ausweichen zu können. Einmal eingestiegen und gefangen in der Sphäre der Bilder sollten die Leserinnen und Leser die Entwicklung gleichsam rückwärts durchschreiten. Aus dem absoluten, ungegenständlichen Raum, der ganz ohne Figur auskommt, lässt sich gut zurückblicken auf die Auseinandersetzung des Malers mit der menschlichen Gestalt im Bildraum und, noch weiter zurück, auf die Vergangenheit und die Bearbeitung gegenständlicher Sujets. Aber wie konnte ein begleitender Text das alles erläutern?

Geccelli hat immer bezweifelt, dass sich geeignete Worte für seine Malerei finden lassen. Ein Künstler darf so etwas sagen; für eine Autorin wäre es eine Bankrotterklärung und Anlass genug, den Beruf zu wechseln. Weil der Maler selbst auch Lehrer und philosophisch gebildet war, könnte man leicht verleitet sein, zur sprachlichen Erläuterung der Bilder ein gleichsam didaktisches oder dialektisches Konstrukt zu erstellen. Aber würde das ein Publikum überzeugen? Etwas, das sowieso schon schwer zu „verwörtern“ ist, durch eine andere, belehrende oder trocken theoretische Methode vermittelt zu bekommen? Nein!

Allerdings ließ mich die grundsätzliche Idee eines philosophischen Dialogs nicht los. Wie wäre es, wenn sich zwei Personen über das Werk unterhielten und dabei gleichermaßen Tatsachen und Gefühle besprechen würden? Sie könnten Geccelli und seine Malerei einfach in einer freien und fröhlichen Art betrachten, sich die Bälle zuwerfen und so das Wohlwollen eines gespannten Publikums erobern. Wer aber könnten diese beiden Personen sein? Wären es reale Menschen, vielleicht die Stimme des Künstlers selbst? Ich habe lange darüber nachgedacht. Dann stolperte ich über einen Satz des Kunsthistorikers und Philosophen Gottfried Boehm, der in einem seiner zahlreichen Texte über den Künstlerfreund schrieb:

„Die Bilder, die wir vor uns sehen, atmen diesen Geist von Systematik und Abenteuer, von penibler Recherche und sinnlicher Weite. Der Betrachter tut gut daran, dieser Spur des ersten Eindrucks zu folgen, den Weg nachzugehen, den der Künstler in seinen Bildern entwirft.“

Da war für mich klar, wie meine beiden Sprechenden heißen würden: P. R. (Penible Recherche) und S. W. (Sinnliche Weite). Zwei fiktive Personen, die, von mir ausgerüstet mit den notwendigen Fakten, einen erfundenen Dialog führen sollten. Als ich einmal angefangen hatte, diese beiden Personae zu entwickeln und reden zu lassen, konnte ich kaum mehr damit aufhören. Ich konnte sie alles sagen lassen, was ich wollte! Welche Freiheit! Welche Freude! Und das ganz ohne Bevormundung der Leserschaft, die ja selbst entscheiden darf, welche der Argumente und Betrachtungsweisen ihr besser gefallen. Vielleicht dann doch ein ganz klein bisschen didaktisch, wenn man sich vorstellt, dass sich über dieses Sprachexperiment auch der Blick schulen lässt.

Ganz entscheidend war – wie bei jedem Buchprojekt – die Gestaltung der Publikation selbst, die Yvonne Quirmbach wieder einmal großartig, mit überraschenden Ideen übernommen und dadurch das Buch zu einem Ausstellungsraum für die Bilder und zu einer Bühne für den Text gemacht hat. So ist – bei aller Schwierigkeit, die höchst subtilen Oberflächen von Geccellis Malerei mit ihren kaum wahrnehmbaren Balkenstrukturen überhaupt reproduzieren zu können – eine Publikation entstanden, die sehr präsent und physisch anwesend ist. In diese Richtung weist auch der Titel des Buches, den ich zum Schluss fand, als ich über ein Vorwort nachdachte und mir die Besonderheiten dieser Malerei deutlich (sprich: körperlich) vor Augen standen: Wenn es denn bei der Kunstbetrachtung überhaupt je darum geht, eine Rechtfertigung formulieren zu müssen, dann konnte ich nur sagen: Solange das geflügelte Wort „Beam me up, Scotty“ aus der Serie Star Trek (noch?) nicht Wirklichkeit geworden ist, sind Geccellis Bilder relevant, weil sie hier, in und von unserer Welt sind.

© 2025 für die abgebildeten Werke von Johannes Geccelli bei

VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn, sowie Künstlernachlass Johannes Geccelli